A July 2, 2012 post by IMF Economist Manmohan Singh and consultant Peter Stella in the blog Vox revisits a familiar topic: the velocity of collateral. We’ve written about this before, often citing Singh’s work. We have some thoughts about the article to share.

The post does a nice job of explaining why it is so important to understand re-hypothecation: it creates money. They write, “…We start from two principles: credit creation is money creation, and short-term credit is generally extended by private agents against collateral. Money creation and collateral are thus joined at the hip, so to speak. In the traditional money creation process, collateral consists of central bank reserves; in the modern private money creation process, collateral is in the eye of the beholder…”

Watching the velocity of collateral is akin to tracking the money multiplier. In the cash world the variables are deposits in the banking system and reserve requirements. In the world of collateral, the size of the system is dictated by the length of the collateral chain and haircuts are the new reserves requirements.

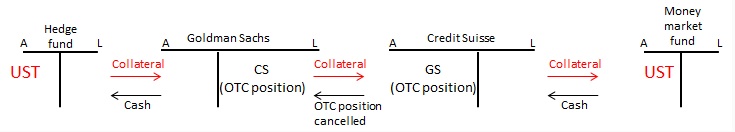

Singh and Stella have an excellent graphic showing an example of a collateral chain. In particular we like how they show different types of transactions ad counterparties could re-use the same collateral — its not just about banks and repos.

They then address de-leveraging. In the banking world, financial de-leveraging happens when loans are repaid (one way or another) and/or cash reserves pile up. In the collateralized world, it happens when haircuts go up, assets fall in value or disappear, or the collateral chain shortens. They cite Singh’s research on overall collateral pledged (i.e. the size of the asset base) going from $10 trillion in 2007 to $5.8 trillion in 2010 and recovering slightly to $6.2 trillion in 2011. Likewise, collateral velocity fell from 3 in 2007, to 2.4 in 2010 and rose modestly to 2.5 in 2011. So far, so good.

Where the article gets interesting and differs from most things on re-hypothecation is when they write about interconnectedness. The fall in collateral velocity means that institutions are lending less collateral between each other. Many would think this is a good thing – after all, when these sorts of trades go bad and a firm is destabilized, the linkages between firms mean they all become riskier. Finadium has written before that repo, and in particular tri-party repo and the clearing process, was seen as the transmission mechanism for systemic risk (a link to a synopsis of the paper is here). But unlike the banks that have been excoriated for not lending money, the credit creation process within the collateralized world has been pushed to shrink. The parallel in the collateralized world to encouraging credit creation would be for the banks to lower haircuts, widen out what is acceptable collateral, and advocate for collateral chains to lengthen. It is an interesting contradiction.

Where we have some issue with the article is when the authors write (collateralized lending) “turns on banks’ trust of each other. New credit gets created only if the onward pledging occurs…Due to heightened counterparty risk, onward pledging may not occur and the collateral thus remains idle in the sense that it creates no extra credit…”

We are not sure if it is just about trust. Collateral chains have shortened and/or volume of collateral pledged has shrunk for a host of reasons. Regulatory constraints including the need to pledge paper to CCPs or hold onto paper to satisfy B-3 liquidity requirements will suck collateral out of the system. In response the Lehman (Europe) collateral issues, more hedge funds (and other institutions that pledge collateral) insist on their paper being held in a legally separate account, sometimes by a tri-party agent. This dead-ends the collateral so that it cannot be re-pledged. Overall lower market activity reduces the need to fund or borrow paper, short circuiting the chain before it starts. One look at the tri-party and securities lending volumes provides ample evidence. Higher capital requirements overall increase friction in the system, slowing down the pace of transactions. And trust (or lack thereof), a result of greater sensitivity to counterparty and collateral credit risk, certainly contributes to lower turnover too. The point is: its not as simple as saying banks don’t trust each other. That is part of it, but not the whole story.

A link to the article is here.